ORDER THE BOOK

PAPERBACK

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books-a-Million

Bookshop

Powells

Walmart

E-BOOK

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Apple Books

eBooks.com

Google Play

Kobo

AUDIOBOOK

(Download – Unabridged)

AUDIOBOOK

(Download – Abridged)

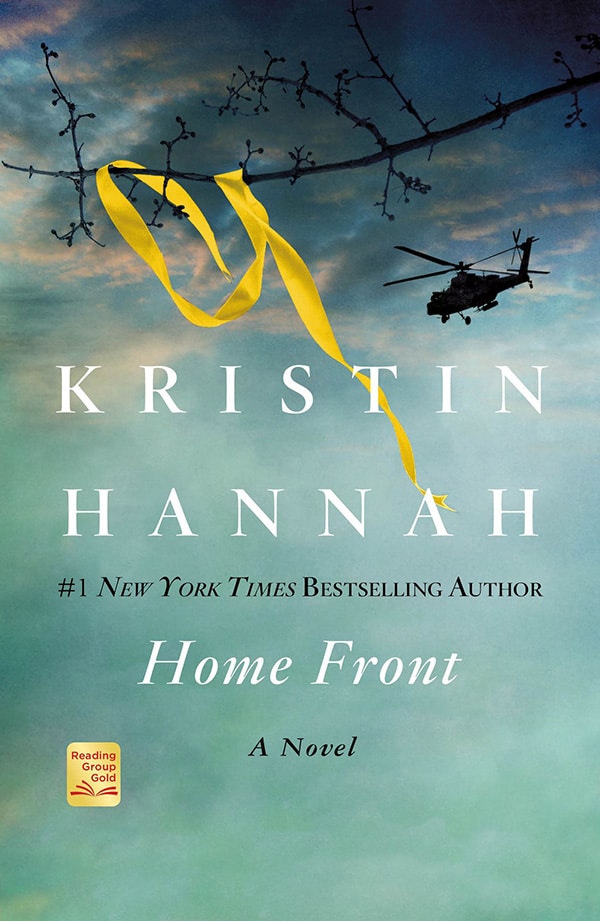

Home Front

Excerpt

Part One

From a Distance

There are some things you learn best in calm, some in storm. — Willa Cather

Prologue

1982

The way she saw it, some families were like well-tended parks, with pretty daffodil borders and big, sprawling trees that offered respite from the summer sun. Others— and this she knew firsthand— were battlefields, bloody and dark, littered with shrapnel and body parts.

She might only be seventeen, but Jolene Larsen already knew about war. She’d grown up in the midst of a marriage gone bad.

Valentine’s Day was the worst. The mood at home was always precarious, but on this day, when the television ran ads for flowers and chocolates and red foil hearts, love became a weapon in her parents’ careless hands. It started with their drinking, of course. Always. Glasses full of bourbon, refilled again and again. That was the beginning. Then came the screaming and the crying, the throwing of things. For years, Jolene had asked her mother why they didn’t just leave him— her father— and steal away in the night. Her mother’s answer was always the same: I can’t. I love him. Sometimes she would cry as she said the terrible words, sometimes her bitterness would be palpable, but in the end it didn’t matter how she sounded; what mattered was the tragic truth of her onesided love.

Downstairs, someone screamed.

That would be Mom.

Then came a crash— something big had been thrown against the wall. A door slammed shut. That would be Dad.

He had left the house in a fury (was there any other way?), slamming the door shut behind him. He’d be back tomorrow or the next day, whenever he ran out of money. He’d come slinking into the kitchen, sober and remorseful, stinking of booze and cigarettes. Mom would rush to him, sobbing, and take him in her arms. Oh, Ralph…you scared me…I’m sorry, give me one more chance, please, you know I love you so much…

Jolene made her way through her steeply pitched bedroom, ducking so she wouldn’t konk her head on one of the rough timbered support beams. There was only one light in here, a bulb that hung from the rafters like the last tooth in an old man’s mouth, loose and wobbly.

She opened the door, listening.

Was it over?

She crept down the narrow staircase, hearing the risers creak beneath her weight. She found her mother in the living room, sitting slumped on the sofa, a lit Camel cigarette dangling from her mouth. Ash rained downward, peppering her lap. Scattered across the floor were remnants of the fight: bottles and ashtrays and broken bits of glass.

Even a few years ago, she would have tried to make her mother feel better. But too many nights like this had hardened Jolene. Now she was impatient with all of it, wearied by the drama of her parents’ marriage. Nothing ever changed, and Jolene was the one who had to clean up every mess. She picked her way through the broken pieces of glass and knelt at her mother’s side.

“Let me have that,” she said tiredly, taking the burning cigarette, putting it out in the ashtray on the floor beside her.

Mom looked up, sad-eyed, her cheeks streaked with tears. “How will I live without him?”

As if in answer, the back door cracked open. Cold night air swept into the room, bringing with it the smell of rain and pine trees.

“He’s back!” Mom pushed Jolene aside and ran for the kitchen. I love you, baby, I’m sorry, Jolene heard her mother say.

Jolene righted herself slowly and turned. Her parents were locked in one of those movie embraces, the kind reserved for lovers reuniting after a war. Her mother clung to him desperately, grabbing the plaid wool of his shirt.

Her father swayed drunkenly, as if held up by her alone, but that was impossible. He was a huge man, tall and broad, with hands like turkey platters; mom was as frail and white as an eggshell. It was from him that Jolene got her height.

“You can’t leave me,” her mother sobbed, slurring the words.

Her father looked away. For a split second, Jolene saw the pain in his eyes— pain, and worse, shame and loss and regret.

“I need a drink,” he said in a voice roughened by years of smoking unfi ltered cigarettes.

He took her mother’s hand, dragged her through the kitchen. Looking dazed but grinning foolishly, her mother stumbled along behind him, heedless of the fact that she was barefooted.

It wasn’t until he opened the back door that Jolene got it. “No!” she yelled, scrambling to her feet, running after them.

Outside, the February night was cold and dark. Rain hammered the roof and ran in rivulets over the edges of the eaves. Her father’s leased logging truck, the only thing he really cared about, sat like some huge black insect in the driveway. She ran out onto the wooden porch, tripping over a chainsaw, righting herself.

Her mother paused at the car’s open passenger door, looked at her. Rain plastered the hair across her hollow cheeks, made her mascara run. She lifted a hand, pale and shaking, and waved.

“Get out of the rain, Karen,” her father yelled, and her mother complied instantly. In a second, both doors slammed shut. The car backed up, turned onto the road, drove away.

And Jolene was alone again.

Four months, she thought dully. Only four more months and she would graduate from high school and be able to leave home.

Home. What ever that meant.

But what would she do? Where would she go? There was no money for college, and what money Jolene saved from work her parents invariably found and “borrowed.” She didn’t even have enough for first month’s rent.

She didn’t know how long she stood there, thinking, worrying, watching rain turn the driveway to mud; all she really knew was that at some point she became aware of an impossible, unearthly flash of color in the night.

Red. The color of blood and fire and loss.

When the police car pulled up into her yard, she wasn’t surprised. What surprised her was how it felt, hearing that her parents were dead.

What surprised her was how hard she cried.

One

April 2005

On her forty-first birthday, as on every other day, Jolene Zarkades woke before the dawn. Careful not to disturb her sleeping husband, she climbed out of bed, dressed in her running clothes, pulled her long blond hair into a ponytail, and went outside. It was a beautiful, blue-skied spring day. The plum trees that lined her driveway were in full bloom. Tiny pink blossoms floated across the green, green field. Across the street, the Sound was a deep and vibrant blue. The soaring, snow- covered Olympic mountains rose majestically into the sky.

Perfect visibility.

She ran along the beach road for exactly three and a half miles and then turned for home. By the time she returned to her driveway, she was red-faced and breathing hard. On her porch, she picked her way past the mismatched wood and wicker furniture and went into the house, where the rich, tantalizing scent of French roast coffee mingled with the acrid tinge of wood smoke.

The first thing she did was to turn on the TV in the kitchen; it was already set on CNN. As she poured her coffee, she waited impatiently for news on the Iraq war.

No heavy fighting was being reported this morning. No soldiers— or friends— had been killed in the night.

“Thank God,” she said. Taking her coffee, she went upstairs, walking past her daughters’ bedrooms and toward her own. It was still early. Maybe she would wake Michael with a long, slow kiss. An invitation.

How long had it been since they made love in the morning? How long since they’d made love at all? She couldn’t remember. Her birthday seemed a perfect day to change all that. She opened the door. “Michael?”

Their king-sized bed was empty. Unmade. Michael’s black tee shirt— the one he slept in— lay in a rumpled heap on the floor. She picked it up and folded it in precise thirds and put it away. “Michael?” she said again, opening the bathroom door. Steam billowed out, clouded her view.

Everything was white—tile, toilet, countertops. The glass shower door was open, revealing the empty tile interior. A damp towel had been thrown carelessly across the tub to dry. Moisture beaded the mirror above the sink.

He must be downstairs already, probably in his office. Or maybe he was planning a little birthday surprise. That was the kind of thing he used to do…

After a quick shower, she brushed out her long wet hair, then twisted it into a knot at the base of her neck as she stared into the mirror. Her face—like everything about her—was strong and angular: she had high cheekbones and heavy brown brows that accentuated wide-set green eyes and a mouth that was just the slightest bit too big. Most women her age wore makeup and colored their hair, but Jolene didn’t have time for any of that. She was fine with the ash-gold blond hair that darkened a shade or two every year and the small collection of lines that had begun to pleat the corners of her eyes.

She put on her flight suit and went to wake up the girls, but their rooms were empty, too.

They were already in the kitchen. Her twelve-year-old daughter, Betsy, was helping her four-year-old sister, Lulu, up to the table. Jolene kissed Lulu’s plump pink cheek.

“Happy birthday, Mom,” they said together.

Jolene felt a stinging, burning love for these girls and her life. She knew how rare such moments were. How could she not, raised the way she’d been? She turned to her daughters, smiling—beaming, really. “Thanks, girls. It’s a beautiful day to turn forty-one.”

“That’s so old,” Lulu said. “Are you sure you’re that old?”

Laughing, Jolene opened the fridge. “Where’s your dad?”

“He left already,” Betsy said.

Jolene turned. “Really?”

“Really,” Betsy said, watching her closely.

Jolene forced a smile. “He’s probably planning a surprise for me after work. Well. I say we have a party after school. Just the three of us. With cake. What do you say?”

“With cake!” Lulu yelled, clapping her plump hands together.

Jolene could let herself be upset about Michael’s forgetfulness, but what would be the point? Happiness was a choice she knew how to make. She chose not to think about the things that bothered her; that way, they disappeared. Besides, Michael’s dedication to work was one of the things she admired most about him.

“Mommy, Mommy, play patty- cake!” Lulu cried, bouncing in her seat.

Jolene looked down at her youngest. “Someone loves the word cake.”

Lulu raised her hand. “I do. Me!”

Jolene sat down next to Lulu and held out her hands. Her daughter immediately smacked her palms against Jolene’s. “Pattycake, pattycake, baker’s man, make me a . . .” Jolene paused, watching Lulu’s face light up with expectation.

“Pool!” Lulu said.

“Make me a pool as fast you can. Dig it and scrape it and fill it with blue, and I’ll go swimming with my Lu- lu.” Jolene gave her daughter one last pat of the hands and then got up to make breakfast. “Go get dressed, Betsy. We leave in thirty minutes.”

Precisely on time, Jolene ushered the girls into the car. She drove Lulu to preschool, dropped her off with a fierce kiss, and then drove to the middle school, which sat on the knoll of a huge, grassy hillside. Pulling into the carpool lane, she slowed and came to a stop.

“Do not get out of the car,” Betsy said sharply from the shadows of the backseat. “You’re wearing your uniform.”

“I guess I don’t get a pass on my birthday.” Jolene glanced at her daughter in the rearview mirror. In the past few months, her lovable, sweet-tempered tomboy had morphed into this hormonal preteen for whom everything was a potential embarrassment—especially a mom who was not sufficiently like the other moms. “Wednesday is career day,” she reminded her.

Betsy groaned. “Do you have to come?”

“Your teacher invited me. I promise not to drool or spit.”

“That is so not funny. No one cool has a mom in the military. You won’t wear your flight suit, will you?”

“It’s what I do, Betsy. I think you’d—”

“What ever.” Betsy grabbed up her heavy backpack—not the right one, apparently; yesterday she’d demanded a new one—and climbed out of the car and rushed headlong toward the two girls standing beneath the flagpole. They were what mattered to Betsy these days, those girls, Sierra and Zoe. Betsy cared desperately about fitting in with them. Apparently, a mother who flew helicopters for the Army National Guard was très embarrassing.

As Betsy approached her old friends, they pointedly ignored her, turning their backs on her in unison, like a school of fish darting away from danger.

Jolene tightened her grip on the steering wheel, cursing under her breath.

Betsy looked crestfallen, embarrassed. Her shoulders fell, her chin dropped. She backed away quickly, as if to pretend she’d never really run up to her once-best friends in the first place. Alone, she walked into the school building.

Jolene sat there so long someone honked at her. She felt her daughter’s pain keenly. If there was one thing Jolene understood, it was rejection. Hadn’t she waited forever for her own parents to love her? She had to teach Betsy to be strong, to choose happiness. No one could hurt you if you didn’t let them. A good offense was the best defense.

Finally, she drove away. Bypassing the town’s morning traffic, she took the back roads down to Liberty Bay. At the driveway next to her own, she turned in, drove up to the neighboring house—a small white manufactured home tucked next to a car-repair shop—and honked the horn.

Her best friend, Tami Flynn, came out of house, already dressed in her flight suit, with her long black hair coiled into a severe twist. In her flight suit and sand-colored boots, she looked almost exactly as she had when they’d met twenty-plus years ago. Jolene would swear that not a single wrinkle had creased the coffee-colored planes of Tami’s broad face. Tami swore it was because of her Native American heritage.

Tami was the sister Jolene had never had. They’d been teenagers when they met—a pair of eighteen-year-old girls who had joined the army because they didn’t know what else to do with their lives. Both had qualified for the high school to flight school helicopter-pilot training program.

A passion for flying had brought them together; a shared outlook on life had created a friendship so strong it never wavered. They’d spent ten years in the army together and then moved over to the Guard when marriage—and motherhood—made active duty difficult. Four years after Jolene and Michael moved into the house on Liberty Bay, Tami and Carl had bought the land next door.

Tami and Jolene had even gotten pregnant at the same time, sharing that magical nine months, holding each other’s fears in tender hands. Their husbands had nothing in common, so they hadn’t become one of those best friends who traveled together with their families, but that was okay with Jolene. What mattered most was that she and Tami were always there for each other. And they were.

I’ve got your six literally meant that a helicopter was behind you, flying in the six o’clock position. What it really meant was I’m here for you. I’ve got your back. That was what Jolene had found in the army, and in the Guard, and in Tami. I’ve got your six.

The Guard had given them the best of both worlds—they got to be full-time moms who still served their country and stayed in the military and flew helicopters. They flew together at least two mornings a week, as well as during their drill weekends. It was the best part-time job on the planet.

Tami climbed into the passenger seat and slammed the door shut. “Happy birthday, flygirl.”

“Thanks,” Jolene grinned. “My day, my music.” She cranked up the volume on the CD player and Prince’s “Purple Rain” blared through the speakers.

They talked all the way to Tacoma, about everything and nothing; when they weren’t talking, they were singing the songs of their youth— Prince, Madonna, Michael Jackson. They passed Camp Murray, home to the Guard, and drove onto Camp Lewis, where the Guard’s flight facilities were housed.

In the locker room, Jolene retrieved the heavy flight bag full of survival equipment. Slinging it over her shoulder, she followed Tami to the desk, confirmed her additional flight-training period, or AFTP; signed up to be paid; and then headed out to the tarmac, putting on her helmet as she walked.

The crew was already there, readying the Black Hawk for flight. The helicopter looked like a huge bird of prey against the clear blue sky. She nodded to the crew chief, did a quick preflight check of her aircraft, conducted a crew briefing, and then climbed into the left side of the cockpit and took her seat. Tami climbed into the right seat and put on her helmet.

“Overhead switches and circuit breakers, check,” she said, powering up the helicopter. The engines roared to life; the huge rotor blades began to move, slowly at first and then rotating fast, with a high-pitched whine.

“Guard ops. Raptor eighty-nine, log us off ,” Jolene said into her mic. Then she switched frequencies. “Break, Tower. Raptor eighty-nine, ready for departure.”

Jolene began the exquisite balancing act it took to get a helicopter airborne. The aircraft climbed slowly into the air. She worked the controls expertly—her hands and feet in constant motion. They rose into the blue and cloudless sky, where heaven was all around her. Far below, the flowering trees were a spectacular palette of color. A rush of pure adrenaline coursed through her. God, she loved it up here.

“I hear it’s your birthday, Chief,” said the crew chief, through the comm.

“Damn right it is,” Tami said, grinning. “Why do you think she has the controls?”

Jolene grinned at her best friend, loving this feeling, needing it like she needed air to breathe. She didn’t care about getting older or getting wrinkles or slowing down. “Forty-one. I can’t think of a better way to spend it.”

. . .

The small town of Poulsbo, Washington, sat like a pretty little girl along the shores of Liberty Bay. The original settlers had chosen this area because it reminded them of their Nordic homeland, with its cool blue waters, soaring mountains, and lush green hillsides. Years later, those same founding fathers had begun to build their shops along Front Street, embellishing them with Scandinavian touches. There were cutwork rooflines and scrolled decorations everywhere.

According to Zarkades family legend, the decorations had spoken to Michael’s mother instantly, who swore that once she walked down Front Street, she knew where she wanted to live. Dozens of quaint stores—including the one his mother owned—sold overpriced knickknacks to tourists.

It was less than ten miles from downtown Seattle, as a crow flew, although those few miles created a pain-in-the-ass commute. Sometime in the past few years, Michael had stopped seeing the Norwegian cuteness of the town and began to notice instead the long and winding drive from his house to the ferry terminal on Bainbridge Island and the stop-and- go midweek traffic.

There were two routes from Poulsbo to Seattle—over land and over water. The drive took two hours. The ferry ride was a thirty-five-minute crossing from the shores of Bainbridge Island to the terminal on Seattle’s wharf.

The problem with the ferry was the wait time. To drive your car onboard, you had to be in line early. In the summer, he often rode his bike to work; on rainy days like today—which were so plentiful in the Northwest—he drove. And this had been an especially long winter and a wet spring. Day after gray day, he sat in his Lexus in the parking lot, watching daylight crawl up the sides of Mount Rainier and along the wavy surface of the Sound. Then he drove aboard, parked in the bowels of the boat, and went upstairs.

Today, Michael sat on the port side of the boat at a small formica table, with his work spread out in front of him; the Woerner deposition. Post-it notes ran like yellow piano keys along the edges, each one highlighting a statement of questionable veracity made by his client.

Lies. Michael sighed at the thought of undoing the damage. His idealism, once so shiny and bright, had been dulled by years of defending the guilty.

In the past, he would have talked to his dad about it, and his father would have put it all in perspective, reminding Michael that their job made a diff erence.

We are the last bastian, Michael, you know that—the champions of freedom. Don’t let the bad guys break you. We protect the innocent by protecting the guilty. That’s how it works.

I could use a few more innocents, Dad.

Couldn’t we all? We’re all waiting for it…that case, the one that matters. We know, more than most, how it feels to save someone’s life. To make a difference. That’s what we do, Michael. Don’t lose the faith.

He looked at the empty seat across from him.

It had been eleven months now that he’d ridden to work alone. One day his father had been beside him, hale and hearty and talking about the law he loved, and then he’d been sick. Dying.

He and his father had been partners for almost twenty years, working side by side, and losing him had shaken Michael deeply. He grieved for the time they’d lost; most of all, he felt alone in a way that was new. The loss made him look at his own life, too, and he didn’t like what he saw.

Until his father’s death, Michael had always felt lucky, happy; now, he didn’t.

He wanted to talk to someone about all this, share his loss. But with whom? He couldn’t talk to his wife about it. Not Jolene, who believed that happiness was a choice to be made and a smile was a frown turned upside down. Her turbulent, ugly childhood had left her impatient with people who couldn’t choose to be happy. Lately, it got on his nerves, all her buoyant it-will-get-better platitudes. Because she’d lost her parents, she thought she understood grief, but she had no idea how it felt to be drowning. How could she? She was Tefl on strong.

He tapped his pen on the table and glanced out the window. The Sound was gunmetal gray today, desolate looking, mysterious. A seagull floated past on a current of invisible air, seemingly in suspended animation.

He shouldn’t have given in to Jolene, all those years ago, when she’d begged for the house on Liberty Bay. He’d told her he didn’t want to live so far from the city—or that close to his parents, but in the end he’d given in, swayed by her pretty pleas and the solid argument that they’d need his mother’s help in babysitting. But if he hadn’t given in, if he hadn’t lost the where-we-live argument, he wouldn’t be sitting here on the ferry every day, missing the man who used to meet him here…

As the ferry slowed, Michael got up and collected his papers, putting the deposition back in the black lambskin briefcase. He hadn’t even looked at it. Merging into the crowd, he made his way down the stairs to the car deck. In minutes, he was driving off the ferry and pulling up to the Smith Tower, once the tallest building west of New York and now an aging, gothic footnote to a city on the rise.

In Zarkades, Antham, and Zarkades, on the ninth floor, everything was old—floors, windows in need of repair, too many layers of paint— but, like the building itself, there was history here, and beauty. A wall of windows overlooked Elliott Bay and the great orange cranes that loaded containers onto tankers. Some of the biggest and most important criminal trials in the past twenty years had been defended by Theo Zarkades, from these very offices. At gatherings of the bar association, other lawyers still spoke of his father’s ability to persuade a jury with something close to awe.

“Hey, Michael,” Helen, the receptionist said, smiling up at him. He waved and kept walking, past the earnest para legals, tired legal secretaries, and ambitious young associates. Everyone smiled at him, and he smiled back. At the corner office—previously his father’s and now his—he stopped to talk to his secretary. “Good morning, Ann.”

“Good morning, Michael. Bill Antham wanted to see you.”

“Okay. Tell him I’m in.”

“You want some coffee?”

“Yes, thanks.”

He went into his office, the largest one in the fi rm. A huge window looked out over Elliott Bay; that was really the star of the room, the view. Other than that, the office was ordinary—bookcases filled with law books, a wooden floor scarred by decades of wear, a pair of overstuffed chairs, a black suede sofa. A single family photo sat next to his computer, the only personal touch in the space.

He tossed his briefcase onto the desk and went to the window, staring out at the city his father had loved. In the glass, he saw a ghostly image of himself—wavy black hair, strong, squared jaw, dark eyes. The image of his father as a younger man. But had his father ever felt so tired and drained?

Behind him, there was a knock, and then the door opened. In walked Bill Antham, the only other partner in the firm, once his father’s best friend. In the months since Dad’s death, Bill had aged, too. Maybe they all had.

“Hey, Michael,” he said, limping forward, reminding Michael with each step that he was well past retirement age. In the last year, he’d gotten two new knees.

“Have a seat, Bill,” Michael said, indicating the chair closest to the desk.

“Thanks.” He sat down. “I need a favor.”

Michael returned to his desk. “Sure, Bill. What can I do for you?”

“I was in court yesterday, and I got tapped by Judge Runyon.”

Michael sighed and sat down. It was common for criminal defense attorneys to be assigned cases by the court— it was the old, if you require an attorney and cannot afford one bit. Judges often assigned a case to what ever lawyer happened to be there when it came up. “What’s the case?”

“A man killed his wife. Allegedly. He barricaded himself in his house and shot her in the head. SWAT team dragged him out before he could kill himself. TV filmed a bunch of it.”

A guilty client who had been caught on TV. Perfect. “And you want me to handle the case for you.”

“I wouldn’t ask . . . but Nancy and I are leaving for Mexico in two weeks.”

“Of course,” Michael said. “No problem.”

Bill’s gaze moved around the room. “I still expect to find him in here,” he said softly.

“Yeah,” Michael said.

They looked at each other for a moment, both remembering the man who had made such an impact on their lives. Then Bill stood, thanked Michael again, and left.

After that, Michael dove into his work, letting it consume him. He spent hours buried in depositions and police reports and briefs. He had always had a strong work ethic and an even stronger sense of duty. In the rising tide of grief, work had become his life ring.

At three o’clock, Ann buzzed him on the intercom. “Michael? Jolene is on line one.”

“Thanks, Ann.”

“You did remember that it’s her 40th birthday today, right?”

Shit.

He pushed back from his desk and grabbed the phone. “Hey, Jo. Happy birthday.”

“Thanks.”

She didn’t scold him for forgetting, although she knew he had. Jolene had the tightest grip on her emotions of anyone he’d ever seen, and she never ever let herself get mad. He sometimes wondered if a good fight would help their marriage, but it took two to fight. “I’ll make it up to you. How about dinner at that place above the marina? The new place?”

Before she could offer some resistance (which she always did if something wasn’t her idea), he said, “Betsy is old enough to watch Lulu for two hours. We’ll only be a mile away from home.”

It was an argument that had been going on for almost a year now. Michael thought a twelve-year-old could babysit; Jolene disagreed. As with everything in their life, Jolene’s vote was the one that counted. He was used to it…and sick of it.

“I know how busy you are with the Woerner case,” she said. “How about if I feed the girls early and settle them upstairs with a movie and then make us a nice dinner? Or I could pick up takeout from the bistro; we love their food.”

“Are you sure?”

“What matters is that we’re together,” she said easily.

“Okay,” Michael said. “I’ll be home by eight.”

Before he hung up the phone, he was thinking of something else.